Sudan’s Aromatic Culture

On Sunday 9 July 2011, South Sudan seceded from Sudan and became the world’s youngest country. The conflict in Sudan has been well documented, but little attention has been paid to the crafts and arts of Sudan. Few people realize what a rich reservoir to the aromatic past Sudan is, and that Sudan once played a vital role in history of Perfumery and the trade of aromatics. Even today Sudan has a thriving aromatic culture with a unique way of making perfumes.

To get a perspective of Sudan’s rich aromatic culture one has to look back into the History of Sudan and its important geographical position that served as a route of passage for people, trade, and ideas since ancient times. The culture of Sudan is a melting pot of fusion between different cultures. The immigrant Arab culture and the neighboring cultures (mainly Egyptian and West African cultures) have strongly influenced Sudanese culture. Their influences are especially evident in the North, West and East of the Sudan. Their influence was less felt South Sudan.

Sudan emerged from some of the world’s oldest civilizations and served as a crossroad for others, namely ancient Egypt, Christian and Islamic civilizations. Its history extends further back than 7000 B.C. The fabled kingdoms of Kerma and Kush (also referred to as Nubia), and many now also believe Punt (South-East Sudan – Beja lands) once rose and fell within the borders of Sudan. At one point, the kings of Kush ruled the entire Nile Valley from the Mediterranean Sea to the Highlands of Ethiopia.

Looking back at Sudan’s origins one may well wonder whether the ancient civilizations of Sudan may have given birth to Egyptian civilization since archaeologists have discovered one of the oldest cemeteries ever found in Africa – dating back to 7500 B.C. – and the oldest evidence of cattle domestication ever found in the Nile Valley in Northern Sudan. It appears that the Egyptians themselves may have identified the region of Somalia, Eritrea and Southern Sudan as “Ta Khent” (‘Land of the Beginning’ or ‘Ancestral land’). (Ref)

The kingdom of Kerma, one of the world’s oldest civilizations, rose about 5,000 years ago out of a pastoral culture with the first settlements established by at least 7000 B.C. Kerma was known as Ta-Sety (“the Land of the Archers’ Bow”) to the ancient Egyptians. The civilization reached its peak between 2500 B.C to 1500 B.C, when it was conquered by the Pharaohs of Egypt and finally annexed as an Egyptian colony – “The Land governed by the Pharaoh’s Son” - Tuthmosis I. (Ref)

Due to its geographical position, for the15 centuries that the Kerma civilization flourished it was an extraordinarily prosperous empire ruled by a series of powerful kings. During this time Kerma established itself very successfully as a middle-man between sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt that controlled the flow of trade in luxury goods to Egyptian Pharaohs, which included gold, ivory, precious woods, wild animals, slaves and of especial interest to us aromatics. Sudan and South Sudan, shares borders with nine different states; Egypt, Libya, Chad, Central African Republic, Zaire, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Eritrea, and is separated by the Red Sea from Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

Sudan’s geographical position thus provided access to trade routes north, south and east to the Red Sea. If indeed the location of almost mythical Punt was in the region of the Gash Delta, extending from the port of Suakin or Aqiq on the Red Sea coast, west to the Atbara River and south into northern Ethiopia most of the international trade in aromatics in antiquity occurred within the borders of Sudan. Punt was also mentioned in the Bible, and ancient Romans called it Cape Aromatica.

Greek geography, the Meroitic kingdom was known as Ethiopia. The Nubian kingdom at Meroe persisted until the 4th century AD, when it fell to the expanding kingdom of Axum. Meroe was the seat of the great caravan route from North Africa and westward across the Soudan (Ethiopia). From Meroe eastward extended the route by which the wares of southern Arabia and Africa were interchanged. The great wealth of the Kushites arose from this net work of commerce which covered the world of the historical times. The trade routes can still be pointed out by a chain of ruins, extending from the shores of the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean. The cities Adule, Axum, Napatan, Meroe, Thebes and Carthage were the links in the chain.

From Meroe to Memphis the most common object carved or painted in the temples was the incense censor. From our present vantage point it is hard to imagine how important and how big the trade in aromatics was in the antiquity. Every nation of the historical times used frankincense and myrrh in religious ceremonies, cultural rituals and for medicinal purposes. Early writers expounded on how much wealth the Kushites attained from this trade by describing “fountains with the odor of violets,” and “prisoners fettered with gold chains.” (Reference) The great value placed on aromatics early in Sudan’s history can be seen in that already in the Middle Kerma period, grave goods of the kings included perfumed oils and unguents. (Reference)

“all goodly fragrant woods, heaps of myrrh-resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony and pure ivory, green gold of Amu, cinnamon-wood, khesyt-wood, ahmut-incense, senter-incense, eye makeup, apes, monkeys, dogs, skins of the southern panther, and with natives and their children” An inscription from Hathsepsut´s expedition to Punt

This area was also instrumental in the trading of cinnamon in ancient times. There is now a lot archeological evidence that the “Cinnamon Route” began somewhere in the Malay Archipelago, romantically known as the “East Indies,” and crossed the Indian Ocean to the southeastern coast of Africa. The spices may have landed initially at Madagascar from where they were transported to the East African trading ports. Merchants then moved the commodities northward along the coast. When exactly the trade between Southeast Asia and the southeastern coast of Africa began is still open to much debate, however the oldest archaeological remains of the domestic chicken (Galllus gallus) found in Tanzania may give us an indication; the remains dates back to 2,800 BCE. Both the domestic chicken and cinnamon originated in Southeast Asia. The earliest similar evidence in Egypt is not earlier than the New Kingdom period about 1,000 years later. (Ref)

As such an important trade center for aromatics since ancient times, it is therefore not surprising to find that the present day culture of Sudan still includes the use of aromatics in all its important cultural and spiritual ceremonies. Looking at the aromatic culture of Sudan gives us a very good indication of the role that aromatics once played in the spiritual and cultural history of humanity, both inside and outside the continent. Perfume production is one of the ancient arts. Although the use of perfume is well recorded in texts from the Egyptian Old Kingdom and the early second millennium in Mesopotamia and Palestine, the sources gives us little precise data about early perfume technology. Thus while the history of the use of perfumes is widely known, the processes and equipment used by perfumers remain obscure. (Ref)

So often in written recipes, techniques that are considered self-evident and common knowledge in the time period, is not recorded and thus becomes lost in time. As the culture of Sudan is almost a microcosm of synthesis of the most influential cultures in the cultural evolution of humanity, I believe that the processes used by the Sudanese in their perfume making contain many of those lost secrets of the ancient art.

The burning of incense to invoke spirits and to dispel negative influences appears throughout cultures and history of the world, whereas the use of perfume oils is traditionally used to make “holy,” or to anoint. Sudan is a wonderful time capsule for the traditional use of incense and perfumes. For a long time I wondered how to capture the burning incense note, and the wonderful scent of fragrant wood smoke, naturally; the techniques used by the Sudanese gave me the answer. More about that later in this article.

Bakhur - Incense

There are two popular methods of incensing in the Muslim Sudan; the bakhra and the takhriga. Bakhra is a sheet of white paper on which the fakir writes astrological formulas, magical seals, or numerical squares, with holy verses from the Quran. A bakhra is burnt in a mubkhar (incense burner), alone or with frankincense and ambergris. The patient bends over the incense burner, covered in a cloth and inhales the fumes. The process is usually accompanied by incantations, a spitting cure, or other forms of treatment.

The takhriga is a blend of herbs, spices, resins and other aromatic ingredients of which bakhur al-taiman (the twin’s incense) is the most widely used. Traditionally the ingredients includes various minerals (even ground coloured stones) and aromatic herbs such as qarad (Acacia nilotica - sunt pods), ‘ain al-‘arus (Abrus precatorius), kasbara (coriander), cumin, Frankincense, Commiphora pedunculata, ghasoul (Salicornia sp.), harmal (wild rue - Peganum harmala), shebb (alum), harjal (Solenostema argel), um gheleghla (Astrochlaena lachnosperma), ganzabil (ginger), mahareb (Cymbopogon nercitus), and sugar. Dufr (operculum) and ambergris is also used in some blends. The takhriga is burnt mainly to expel the evil eye and subsequently protect against its influence and to undo magical spells. Incantations are recited while dusting the ingredients over the fire. The inflicted person has to wash his or her feet in rigla (purslane) water before undergoing the incense therapy. (Reference)

Several times, I escaped my parents’ notice, and sometimes-even school, to sneak into one of the zar houses. I found the ceremonies fascinating, and still remember them vividly, and with pleasure. The rhythm of the zar music and the heavy fragrances that escape from the ceremony houses are unforgettable. - Dr Ahmad Al Safi, author of Traditional Sudanese Medicine

Although the Zar rituals have been officially banned in the Sudan since1992, and Zar ceremonies were driven underground in Egypt during the 1940s and 1950s with practioners fearing persecution from a society that did not understand the complexities of Sudanese mysticism, the ‘drums’ still beat the rhythms of the mystical, soul-cleansing ceremonies and the incense still perfume the air of the Zar houses. (Reference)

Zar Video

The Zar culture is a widespread healing cult found throughout much of northern and north-eastern Africa, predominantly in Islamic areas, as well as in parts of the Middle East. The people of Sudan were converted to Islam at the beginning of the fourteenth century, after the collapse of the Christian kingdom of Donqola in northern Sudan. Muslims represent seventy percent of the population, Christians four percent, and the remaining are animists. The Zar cult incorporates a complex belief system that had evolved over many centuries combining elements of shamanic-type practices along with recognition of Muslim prophets and Christian spirits. (Ref)

The origins of the Zar cult is still a heated debate among scholars, with some even debating that it stems from an earlier belief system derived from Persia. The data collected from fieldwork however, suggest that the Zar cult is pre-Islamic, as the rituals themselves accommodate traditions and customs contrary to Islam and that it seems rather to have originated in Africa. The Zar cult is a cultural phenomenon that link Sudan, Ethiopia, and Nigeria. Although called by different names, it is widespread in Africa even among non-Muslims. Both the music and rituals involved are reminiscent of other African spiritual ceremonies. One can easily imagine the ceremonies as part of the earlier Kingdoms of Sudan. (Ref)

Zar takes various forms in the Sudan; the Zar–Bori cults being particularly associated with women, while Zar–Tumbura is associated more particularly with men. Tumbura is connected with the underwater world, and resembles the Edo spirit possession cult in Benin City, Nigeria. Zar Bori spirits who are connected to the underwater world are related to the Tumbura realm. The Zar Bori spirits belong mainly to dry lands, jungles, and mountains. (Ref)

The Zar spirits are classified into different groups which reflect ethno-cultural groups. These groups appear to be related to ancestral spirits as they reflect the cultures with which the ancient Sudanese had contact with. Among these groups are the Darawish (dervish or Sufi), who are sometimes called AhlAllah, which literally means God’s people; Habash (Ethiopian); and Arabs. (The Sudanese identify nomads as Arabs. In the Sudanese conception, sometimes the term “race” is not necessarily connected with blood relationship, but perceived in social and geographical terms.) Next in the Zar groups are Pashawat (Turko-Egyptian), Khawajat (white, non-Muslim), and Zurg (black or Sudanese). Other Zar characters operate as groups, such as al-banat (the girls). Yet others exist as individuals, such as the “Chinese.” The Zar order of spirits also operates under a hierarchy according to the Zar characters’ political, religious, and social positions. (Reference)

Each of these spirits is recognized by particular characteristics and each spirit has its associated drumbeat, songs, costume and incense. The symbolism of the rite is reminiscent of marriage, for the patient or devotee is called a ‘bride of the Zar’, and she is dressed and perfumed as a bride with a red henna dye applied to her hands and feet. Being the bride, symbolize the potentiality of marriage between the bride and the spirit, also called the “Opening.” The openings give the devotee knowledge of particular skills and therefore power; for example through the knowledge of Wad’i (sea shells) the devotee can read the future and tell secrets. (Reference)

The zar bori parties, also known as midans or dastur (plural dasatir), involve lengthy preparations setting the scene for the musical extravaganza and dancing séances. The zar house is characteristically crowded, and filled with strongly scented fumes and perfumes. The novice, the participants, and the audience are all dressed in their best clothes. The zar novice and devotees join in the dancing.

The majority of Zar cult leaders are women, and they are addressed as Sheikha. The Sheikha is an essential figure in Zar rituals. She is the one who controls the entire situation and mediates between the spirit world and the possessed person. When in a trance, the patient will speak in a spirit voice and through gestures indicate which spirit is possessing her. Through the Sheika, the gestures will be interpreted and the requirements of the spirit ascertained. Often the demands of the spirit will include the mounting of a ritual, with spirit costumes and a sacri?ce in its honour. In addition to the Sheikha, there is the Sheikha’s chorus who helps her by singing and drumming. (Ref)

The Zar session begins with the burning of incense to invoke the spirits. The first procedure in Zar healing is called Fath-al-ilba. This refers to the opening (fath) of a tin. The ‘ellba’ (tin box) symbolizes the Sheikha’s power, and represents the communication between her and the spirit world. The ‘ellba’ is given as a gift to Sheikha when she is initiated as a cult leader. The ‘ellba’ contains all the different incenses that call and provoke the spirits. As each zar spirit has its appropriate incense, whenever the Sheikha burns incense, she is invoking the appearance of the specific spirit that has possessed the person. The elba calls to mind the tortoise shell boxes of the San which carriers the ingredients for the “medicine smoke.” The second step is to identify the spirit which possesses the victim, and hence activate the process by which the spirits can be controlled by the Haflat al-zar (Zar party). (Ref)

The Sheikha herself makes a ceremony, once every year during the month of Rajab, the month before Sha’aban, called Al-Rajaligya. The Shaikha’s party marks the closing ceremony of the year that has passed, and no Zar is practiced during the months of Shaaban and Ramadan. During this time all the Zar boxes must be closed, and only later opened after Zul-Hajja. The ceremony practiced to close the boxes is called Rajabiyya, a reference to the month Rajab. Every devotee is equipped with incense, which allows her to release herself during the months when the boxes are closed. (Ref)

A typical Zar incense or Bakhur Al-Zar generally contains ‘udiya (Aquilaria agallocha Roxb. - Agarwood), luban jawi (“Frankincense of Java “– Benzoin), Frankincense, Commiphora pedunculata, sandalwood, mastika (mastic gum), ghasoul (Salicornia sp.), murr higazi (Commiphora abyssinica), blended with traditional Sudanese perfumes.

Presenting beauty on a daily basis is the means by which the devotee appeases the spirits, and consequently maintains power given to her by the zar spirits.

According to Baqie Badawi Muhammad in her fascinating paper “The Sudanese Concept of Beauty, Spirit Possession, and Power,” beauty is an essential element in the Zar cult.

“Beauty, while attracting the negative powers, has the potential to be harnessed through spirit possession into a powerful force which can be turned in favor of the devotee. The interaction between the devotee and the spirit galvanizes beauty with protection from evil elements. The guarding of beauty is the beginning and end of this ongoing process. The power of the devotee grows through this maintenance of beauty in rituals that have been endowed through traditional thought with religious significance. Although spirits protect the devotee, any negligence of her own beauty will result in punishment, thereby negatively affecting the devotee’s power.”

Taking care of one’s beauty is essential in sustaining the devotee’s power. In Ethiopia it is often claimed that a woman’s glowing charms leave her when her protective Zar leaves her. Women associate some spirit characters with cleanliness and sweet smells. Thus bad smells are said to provoke jinn, and therefore endanger body well-being. One spirit called Tahashaw often resembles a northern Sudanese woman with strong provoking perfume accompanied by the rattling sound of her jewelry. (Ref)

The burning of incense and the use of perfumes therefore also play an important role in creating an aesthetic environment that pleases the Zar spirits.

Perfumes and Cosmetics

Sudanese women have unique local perfumes and cosmetic rituals, such as; Khumra, dilka, Karkar, Dukhan, and henna decoration. These cosmetics can only be used by women who are married or about to get married.

The traditional Sudanese perfume is called Khumra and the word is said to be derived from the word khamara “to cover” and could also be derived from the verb “khaamara”, which means mix up (whether confused or literally mix up). The origins of the word is a lovely description of Sudanese “potpourri” which forms the basis of the Sudanese perfumes

I find the techniques and ingredients used fascinating as it represents for me a slice in the history of perfumes. It could well represent how perfumes were first made in ancient Egypt and the Nubian civilization. Before I delve into the traditional perfumes and cosmetics, I will cover some of the ingredients that add a historical perspective.

Mahleb cherry kernels

Mahlab - Prunus Mahaleb

“Mahlab” or “Mahleb” is an essential ingredient in both Khumra and Dilka (I will cover Dilka separately.) Mahleb was once widely used by Arabian and Persian perfumers who also used it as an ingredient for incenses, and although no mention is made of its use in ancient Egypt I see no reason why they would not also have used it, as the spice is widely used in Egypt. I have to wonder whether the “red berries” in the famous Egyptian Reliefs that depict some of the aspects of perfume making on the walls of the tomb of Petosiris from the early Ptolemaic period could not have been Mahlab cherries?

Today,

however, Mahlab seems to be used almost exclusively as perfume

ingredient in Sudan. Mahleb appears to be one of those “forgotten

perfume ingredients,” as it is now used principally in the Middle East,

Egypt, Greece and Turkey as a ground spice for dips, bread, pastries,

and sweetmeats. In Italy it is also used to make Liquore di amarenelle. (Ref)

Mahlab is the kernel of a species of wild cherry, Prunus mahaleb, also known as the Perfumed cherry, or St. Lucie cherry. Mahaleb cherrry is native to Morocco, Iran, Iraq, Armenia, Pakistan, Caucasus, Soviet Middle Asia, Central and Southern Europe. The major producer of Mahlab today is Iran, followed by Turkey and Syria. Mahlep cherry is seen as the mother of cultivated cherries, since the mahlep cherry is often used as the grafting stock for table cherries.

The

aroma of Mahleb is described as rose-scented with a subtle flavour of

tonka beans or bitter almond with a hint of cherry; much like marzipan

with a floral quality to it. The scent and taste description is not

surprising since coumarines appears to be the main flavour compounds of

the kernels, one of the most common ingredients in many perfumes.

Coumarin has also been isolated from the dried bark, wood, and leaves.

It has also been found to contain glycosidically bound

4-methoxyethyl-cinnamate. In Sudan the oil extracted from Mahlab is

called Baida. Mahlabiya oil said to be derived from Mahlab is commonly

used to darken Henna decorations. (Ref)

Dufr ‘fingernails of the sea’

Another interesting ingredient used in the perfumes is called dufr, “fingernails of the sea” and can also be considered a historical ingredient, rarely used today. Dufr is also used in Sudan for treating fever, wasting disease, and as a fertility symbol, and for amulets. It curious indeed that it is called “Fingernails of the sea” which leads directly to Onycha,” the ancient Greek word for “Finger Nail,” which comes from an early translation of the Old Testament into Greek, from the original Hebrew word; “shecheleth” meaning nail, claw or hoof, of the much debated ingredient used as an incense material in the Book of Exodus. Onycha from the bible is very likely the same as dufr; the horny operculum found in certain species of marine gastropod mollusks. The most likely candidates for the biblical onycha are; Strombus lentiginosus, Murex anguliferus, Onyx marinus, and Unguis odoratus. (Ref)

Hiroshi Nawata has done extensive historical and ethnographical studies on trade in operculum of gastropods in Sudan and has concluded that operculum as incense and perfumery ingredient was exported since historical times from the ancient port of Badi, which was situated in South Eastern Sudan on the Red Sea coast. Badi was an important port-town for historical Red Sea trade. Commodities from the African interior, as well as coastal products such as tortoise shell, pearl and mother-of-pearl, sponges and corals, shark fin, shell, crab, and fish were traded from Badi. Opercula are still harvested from around al-Rih island where Badi was situated, and still helps the cash income of the Beja people. Three kinds of opercula from the Red Sea are used and traded, but the opercula of Strombus tricornis are considered the best in Africa and the Middle East. Opercula (dufr) are still widely used in incenses and karkar, dukhan, dilka, khumra and bahr muassal among the contemporary Sudanese people. Cuttle-fish bone called Zabab Malih, is also used in Sudan, powdered and mixed with kohl. Used in treating eye inflammation (Ref)

Although

I could find no reference of how dufr is prepared for use in Sudan,

descriptions of how it was prepared in other parts of the world will be a

useful indication. Writers during the Middle Ages recorded that onycha

was rubbed with an alkali solution prepared from the bitter vetch

(Lathyrus linifolius) to remove impurities. It was then soaked in the

fermented berry juice of the Caper shrub, or a strong white wine. This

treatment of an alkali solution and then with wine is also reported in

other cultures that uses the operculum. In Japan and China they are

treated with alcohol, vinegar and water, and in the Hebrew tradition,

wine and lye (caustic soda) is used. After this treatment some suggest

to then slowly heat the ground operculum in a pan with just enough oil

or ghee to cover them, taking care not to overheat and burn the

opercula. The active is ingredient is apparently drawn into the oil

which is used as the incense ingredient, and the residue as a fixative.

In Oman and other Middle Eastern countries they are ground to a rough

powder, and a small amount of this is added to the incense mixture. (Ref)

In Tamil the powdered operculum is soaked in water, and used as an adhesive matrix to bind together the powdered sandalwood and other incense material used in coating the incense sticks. The operculem is called naganam or navanam by the Tamil. (Ref)

Musk (Misk) and Ambergris (Anber) are traditionally also used in Sudanese perfumes. Although there are not many references of Civet being used, one research paper on the Trade of Sudanese Natural Medicinals do mention Civet being as perfume ingredient. (Ref: Trade of Sudanese Natural Medicinals and their role in Human and Wildlife Health Care)

This will not surprise me, as it is available from neighbouring Ethiopia. Civet cat farming is an ancient practice in Ethiopia and in its early history. Civet musk was used as currency and traded with Egypt, Zanzibar and India. (Ref) Civet musk was valued above ivory, gold or myrrh. The Queen of Sheba (1013-982 BC) allegedly presented civet musk as a gift to King Solomon Traditionally it was used as a medicine for various ailments and taken in tea and coffee. As Northern Ethiopia was once part of the Kush kingdom and Sudan was a major trade route for aromatics in ancient times Civet would have been part of the valuable trading commodities to pass through its borders and ports. (Ref)

Sandalwood (Santalum album) and Sandalwood oil (Sandaliyya) is widely used as an aromatic ingredient. A crude Sandalwood oil is also sold. Women also make an infusion by scraping sandalwood chips with a knife into coconut or palm oil and macerate it until the oil takes on a red tint. The oil is used to keep the skin soft, moist and protected. It also is used to stop the skin looking ‘grey’.

Frankincense, Myrrh and Mastic gum

Frankincense, Myrrh and Mastic gum has also been a widely used commodity from this area. Mastic gum is thought to be “sntr” incense mentioned in the ancient Egyptian texts of the Punt expeditions by some scholars. The species of Pistachio found in Africa is Pistacia aethiopica, distributed in Somalia, Eritrea and Southern parts of Ethiopia, and Pistacio chinensis var, falcate also occurs in Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan. The odour emitted by Commiphora samharensis is similar to some of the Pistacia species and it is speculated that it is possible that it could have been used as an alternative source of “sntr” or interchangeably by the Egyptians. The myrrh species found in the region are; Commiphora myrrha, C. erythraea, and C. samharensis. Commiphora gileadensis or opobalsamum is widespread in Western and Eastern Sudan and both the twigs and resin is used.

Also mentioned in the Punt texts is “ntyw” which refers to either frankincense or myrrh. The Frankincense species found in Africa are; Boswelia carteri (inland Somalia), Boswelia frereana (coastal regions Somalia), Boswelia papyrifera (Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Central African Republic and Uganda), and Boswelia bhau-dajiana. Boswelia rivae is found in southern Ethiopia and Somalia. The Boswelia species are most likely the source of antyw (ntyw). (Ref; Profiling Punt: Using Trade Relations to Locate” God’s Land” Catherine Lucy)

Dilka - Scented massage

Dilka is used by women as an exfoliating scrub that leaves the skin soft and perfumed. Like Khumra and dukha, dilka is only allowed to be used by married or about to get married women. Unmarried girls are only allowed to use dilkat-burtuqal (orange paste).

It has been noted that women who use dilka frequently, have a supple, clean, fragrant, and healthy skin. John Petherick, a traveler who visited the Sudan in the eighteenth century, submitted unwillingly to this procedure. He described its effects, saying:

“The following morning I woke quite revived; the feverishness had entirely subsided and with a calm and refreshing sensation through my limbs and body.”

The dilka dough is prepared in much the same way as the basis of Khumra and takes about 3-5 days. The principal ingredients are however, sorghum or durra (durum) flour. Alternatively, millet flour or even orange peel is used. It is called dilka murra (bitter) if unscented and hulwa (sweet) if scented. Powdered ‘Mahleb’ (Prunus mahaleb) seeds and cloves are soaked in water and let to steep for several hours. It is then strained through a fine strainer, the seeds discarded and the watery extract gradually added to the flour and kneaded by hand into soft dough.

To the dough, different amounts of finely ground fragrant woods are added such as tahlih wood (Acacia seyal - shittah tree), shaff (Terminalia brownie), and sandalwood, as well as powdered mahlab, qurunful (Cloves), and dufr (operculum) and sometimes zabad (Cuttle-fish bone.) This basic mixture is called al-marbou’ and if luban (Frankincense) and simbil (Spikenard) are added then it is called al-makhmous.

This paste is spread on the inside of a bowl (traditionally wooden). The bowl is then inverted over a container or a dug hole with smoking aromatic woods such as shaff, sandal, and talh. The durra paste is enriched with the fragrant smoke of the woods. At regular intervals, a handful of the powdered fragrant blend mentioned above is added and kneaded in, until the material is cooked and the right fragrance achieved.

Once the paste has cooled to this will be added kabarait, a blend of traditional scents such as musk, surratiyya (Crude oil of cloves), zait sandaliyya (Crude sandal oil), or majmou (clove and sandal oil), and baida (mahleb oil) may be added, as well. To make a special dilka, sugar, favourite liquid perfumes, and zait al-ni’am (Ostrich fat) are also added. Popular perfumes often added are Bint el Sudan and Reve d’ Or (1889) but more about that later.

This is then scraped from the bowl and sometimes further scented by spreading it on top of a mesh and smoking it with bakhur (incense). Otherwise, it is formed into small balls and preserved in huqs (airtight wooden pots) until needed. The smoking also cures the dilka as it stays preserved longer than other types of similar paste.

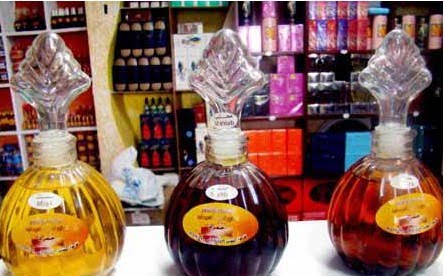

The technique generally used to prepare the traditional perfumes is unique. The smoking of ingredients is unusual and I have not come across it in any other perfumery techniques. First a paste is made from the powdered dried ingredients such as mahleb seeds, cloves, nutmeg, dufr, sandalwood and musk, and sometimes even dried apples studded with cloves and orange peels are added. This paste is then smoked in a charcoal fire with pieces of sandalwood and local aromatic woods. After smoking the paste Frankincense, myrrh and various liquid aromatic oils is added and the smoked paste is then infused in oil to produce the perfume.

The making of perfumes is an important part of Sudanese wedding rituals. The preparations for the wedding perfumes start about a month before the wedding by the women of the bride’s relatives and friends and it is a skill that is passed on by through family members.

The following video shows how Khumra is made.

Khumra demonstration

Dukhan – Body incensing

Dukhan, or smoke bath, is a beautification ritual practiced by women in northern Sudanese provinces. This ritual is also forms a part of the traditional Sudanese wedding preparations. Although women insist on the benefits of dukhan for health reasons such as curing bodily aches, cleanliness, health, and for restoration after childbirth, it has strong associated with sensuality and eroticism. It is believed to boost sexual gratification. The Himba women also use a smoke bath on a daily basis but for cleansing purposes.

A

blend of scented shaff, talih, and sandalwood is placed inside a hole.

Enough charcoal is lit to produce scented smoke. A birish rug, woven

from palm tree branches, with a central opening, is then placed over the

hole. To bathe, a woman strips naked. Her body is thoroughly rubbed

with karkar, scented oil generally made from animal fat, orange peel,

and clove essences. The woman sits over the hole, allowing the rising

smoke to fumigate her body. Women rarely perform dukhan alone. Usually,

they rely on the help of female kin, neighbors, and friends to add wood

as needed or to provide water to compensate for the massive amount of

perspiration during the bath, which can last for an hour or more. The

dilka body scrub is then used to clean the body and to reveal a

glistening skin. A warm shower concludes the process. (Ref)

Men try dukhan occasionally to alleviate rheumatic pain. The wood used in restorative fumigation is usually shaff and talh. When dukhan is performed for therapy, heavy scenting is omitted and various medicinal plants and other items are used instead. (Ref)

The Sudanese have evidently observed that the aromatic oils that exuded from certain plants when they are burnt have beneficial properties other than being restorative and emollient to the skin and body. They have preservative and therapeutic values when burnt. For example, it has been discovered that dukhan (smoking with aromatics) preserves food, straw mats, and woolen covers. Milk pots are sometimes fumigated with kadad (Dichrostachys cinerea) until they become black, and when milk is stored in them it lasts longer before it gets sour and the milk acquires a lovely odour after it has been kept there. (Ref)

Anti-microbial creams are also prepared in this way by the condensation of the aromatic oils by a variety of burnt plants. The volatile oils of lalobe (Balanites aegyptiaca), for example, are absorbed on the inside of a wooden pot smeared with oil. The condensed cream is then scraped and used topically for the treatment of some skin ailments. Luban dhakar (frankincense) is also burnt underneath a small inverted pot. The black fumes condense on the inside, and are scraped into a muk-hala (eye cosmetic pot) and used in beautifying eyes like kohl, and to protect them against various illnesses. Such eye treatment is particularly popular among brides and elderly women. Fenugreek is similarly used; its ointment is used to treat various scalp ailments. (Ref)

Chips of sandalwood coated in sugar are also burned in a small clay dish, which is covered by a dome “cage” of light flexible wood (mabkharah). Clothes are spread on top of the cage so they absorb the fragrant smoke—another tradition done only by married women.

Bint El Sudan

Out of this rich aromatic culture of Sudan was born what is perhaps world’s all time best selling perfume; Bint El Sudan. First introduced in 1920, by the 1960s and 1970s, it was the biggest selling non-alcoholic based perfume in the world and a separate alcoholic-based version was also released. An average of 5.7 million bottles of Bint El Sudan is now produced every year for Africa, according to Nicholas Evans, the IFF fragrance sales manager for Africa.

Alison Bates tells the wonderful story of how her grandfather was instrumental in the birth of Bint El Sudan on her blog.

According to the story Sudanese nomads approached him with vials of precious essences with which to produce an oil based perfume for the Muslim market. The rest of the story is legendary and Bint el Sudan became one of the most recognized fragrances of Africa: The original distribution network was still via camels caravans carried by merchants traveling all over north and West Africa and into the Middle East. It was even used as a currency in the area, and as a result of the value placed on Bint El Sudan counterfeits became rife. The packaging today has been designed to counter act counterfeits but the original label design remains as recognizable as ever.

The original Bush firm has changed hands several times since her grandfather’s day. It was bought by Albright & Wilson in 1961; became part of Bush, Boake and Allen (BBA) in 1966; and in 2000, the U.S. conglomerate International Flavors & Fragrances (IFF) bought out BBA and took over the rights to the Bint formula.

The original Bint

formula was several pages long and no doubt contained a large percentage

of naturals. Since then it has been reworked and synthesized.

Non-alcoholic and alcoholic based versions are sold in different shaped

bottles, and plastic plugs used instead of corks. It is packaged and

distributed in Nigeria, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya,

South Africa, Sudan, Zimbabwe as well as in Saudi Arabia for the Middle

Eastern market. (Ref)

The enduring success of Bint El Sudan must be seen against the background of Sudan’s aromatic culture. It is a popular addition to Khumra, Dilka and is especially associated with weddings and as an aphrodisiac. Just like the other traditional fragrances only married women can use it. It was even marketed in the U.S as “Africa’s Famous Love Fragrance”. It is also reputed to be used to anoint the dead as well for daily use, sprayed on talih wood to scent the home, bed covers and even clothes. I even came across a site advertising it as “Good for purification and meditation.”

Nicholas Evans kindly sent me some samples of Bint El Sudan to smell and filled me in with more back ground stories. So what does Bint El Sudan smell like? The marketing description is; “A blend of floral odours with the emphasis of jasmine, lilac and lily of the valley, with undertones of woody notes supported by musk, amber and moss.” The cute12ml bottles sells for about 1 dollar in Africa. They also sell little triangular bags of Bint el Sudan.

The scent is instantly recognizable as one I have often smelled in public places, also a scent associated with shower-fresh. The fresh Lily of the valley top notes quickly dissipate into notes of rose that I associate with Turkish delight, or sweet rose water with a sparkle of Jasmine Grandiflora note which drifts into notes of sandalwood soap, and finally settles in a base of masky amber. I do not smell much oak moss though.

Sudan’s Aromatic Future

Many

women, in both rural and urban areas, serve as the head of the family

as a result of the massive migration of men from rural areas to cities

or out of the country and the trade in aromatics still help to provide

many women with an income. In the cities, women work as small retailers

for spices, some medicinal and culinary plants and perfumery woods which

remain to be in high demand. Women who make traditional “Khumra” are

usually well paid for this job. Oxfam has also made available small

loans for helping women making Khumra to set up small businesses. One

such success story is featured by Oxfam of Um Hageen Al Agib’s home-made

perfume shops in western Omdurman. Such market stalls sell other local

beauty products, such as soap, face creams, hair oils and henna, as well

as medicinal herbs too. If you click on the picture it will take you to

her story.(Ref)

This year the First Festival for Sudanese Perfumes was held with the theme of ” Sudanese Perfumes: Towards Internationalism,” in Khartoum. The Chairperson of the Sudanese Centre for Development of the Businesswomen, Mrs. Samia Shabo said the Perfumes’ Festival is an attempt to shed light on the various kinds and good quality of Sudanese perfumes as well as their ability to compete other perfumes in the international markets.

The Souk al-Sabit market in Khartoum presents products of the businesswomen in the Khartoum State. The Souk al-Sabit displays various products of perfumes, taobs, bed sheets, cosmetics and whatever relates to women and the family. The markets and festivals help to develop and upgrade the skills of the businesswomen and provide facilities and small funding from the banks. The market has achieved a great success as it availed the opportunity for the businesswomen to know one another and exchange their experiences and expanded their activities from the narrow framework of the housing areas to external markets, and above all else contributed to supporting the poor in the communities

During the Perfumer’s Festival Madame Amal Issa was chosen as the Queen of Perfumes in Sudan. Madame Issa participated in the festival with dozens of Sudanese traditional perfumes. She uses Sudanese materials in her perfume production. Her winning perfumes are born out of her deep passion and love for the Sudanese traditional perfumes. She said that she has inherited her profession from her old ones, the grandmothers, and concluded

“Perfume is like a glimpse of light to me.” (Ref)

Abkab tikati ba fadiga

Don’t let go of what you have - From a Hadendowa Legend

Perfume Festival

Traditional Sudanese Perfumes and Products are available from Lubna Ali

Scented Smoke Enfleurage

Have you not ever wanted to capture the lovely scent of burning frankincense, and other resins and woods to give another dimension to an incense accord? The action of imparting scents onto the fats is called enfleurage; although it is traditionally used with flowers, the Sudanese techniques of perfume and cosmetic making gave me the idea of how to make Scented Smoke Enfleurage.

You will need a dish in which to burn the resins and woods. I use a flat ceramic bowl that often is the base for ceramic flower pots. Or you can just burn it in a hole in the ground.

A heat resistant bowl that will fit just over, or within the burning bowl.

Charcoal used for burning Incense

Palm fat, or any fat that you will use for enfleurage.

Any resins, aromatic woods, spice or dried herbs that you love the burning scent of.

1. Melt the fat inside the bowl and roll the melt fat against the sides so that it is a thin layer rather than just a layer on the bottom of the bowl. Allow it to cool and become hard.

2. Place the charcoal inside the burning dish and light it. Make sure that it is hot before adding the aromatics. When it is giving a good smoke place the bowl with the layer of palm fat over it.

3. Keep checking to see that the fat is not melting or that there is still enough smoke.

4. Keep adding aromatics for more scented smoke until the fat has been thoroughly impregnated with the scent.

5. Then you scrape the scented fat from the bowl and put it inside a jar with enough alcohol to cover. Shake it daily until you feel it is strong enough. You can also recharge by straining the alcohol and placing more scented fat in the alcohol. That way you can make the extract as strong as you want to or even blend different smoky scents.

It is really fun to experiment with different kinds of aromatics. My favourites so far are of course Frankincense, Omumbiri and Camel thorn wood.

http://africanaromatics.com/wordpress/?p=736

The History of Perfumes

Perfume was first used by the Egyptians as part of their religious rituals, after them the Indian are known to use the fragrances. The principal methods of use at this time were the burning of incense and the body application of balms and ointments. Perfumed oils were applied to skin for either cosmetic or medicinal purposes. During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, perfumes were reserved exclusively for religious rituals such as cleansing ceremonies. Then during the New Kingdom (1580-1085 BC) they were used during festivals and Egyptian women also used perfumed creams and oils as toiletries and cosmetics. The use of perfume then spread to Greece, Rome, and the Islamic world. And it was the Islamic world that kept the use of perfumes since the spread of Christianity led to a decline in the use of perfume. With the fall of the Roman Empire, perfume's influence dwindled in western world. It was not until the twelfth century and the development of international trade that this decline was reversed.

Perfumes enjoyed huge success

during the seventeenth century. Perfumed gloves became popular in France and in

1656, the guild of glove and perfume-makers was established. The use of perfume

in France grew steadily. The court of an western emperor was even named "the

perfumed court" due to the scents which were applied daily; not only to the skin

but also to clothing, fans and furniture. The eighteenth century saw a

revolutionary advance in perfumery with the invention of eau de Cologne. This

refreshing blend of rosemary, neroli, bergamot and lemon was used in a multitude

of different ways: diluted in bath water, mixed with sweet drinks to enjoy

refreshing aromas, eaten on a sugar lump, as a mouthwash ... and so on. The

variety of eighteenth-century perfume containers was as wide

as that of the fragrances and their uses. Sponges soaked in scented vinaigres

de toilette were kept in gilded metal vinaigrettes. Liquid perfumes came in

beautiful style pear-shaped bottles. Glass became increasingly popular,

particularly in France.

As with industry and the arts, perfume was to undergo profound change in the nineteenth century. Changing tastes and the development of modern chemistry laid the foundations of perfumery as we know it today. Introduction of sciences of chemistry gave way to chemistry and new fragrances were created. Revolutions around the world had in no way diminished the taste for perfume. Under the post-revolutionary governments, people once again dared to express a penchant for luxury goods, including perfume. A profusion of vanity boxes containing perfumes appeared in the 19th century.

Perfume is thousands of years old - the word "perfume" comes from the Latin per fume "through smoke". One of the oldest uses of perfumes comes form the burning of incense and aromatic herbs used in religious services, often the aromatic gums, frankincense and myrrh, gathered from trees. The Egyptians were the first to incorporate perfume into their culture followed by the ancient Chinese, Hindus, Israelites, Carthaginians, Arabs, Greeks, and Romans. The earliest use of perfume bottles is Egyptian and dates to around 1000 BC. The Egyptians invented glass and perfume bottles were one of the first common uses for glass.

Arabian Perfumes / Attars

There are several perfumes that were introduced by Arabs since ancient times as they were very much found of scents. The passion of fragrances – boosted by their love of the Prophet of Allah (may the Peace and Blessings of Allah be upon Him); since He (SAW) has counted Fragrance among one of the things of this world that He loved; made them go almost everywhere, searching for sources of perfumes: they climbed rocks crossed seas and forests searching for more and more exotic fragrances.

The perfume oils are pure natural oils; also called as Concentrated Perfume Oils. Besides the body application as perfumes, Perfume oils are used in Aromatherapy as well and are used by Arabs and the Muslims in the Middle East, but this use is not limited to a certain part or people of the world anymore but rather Aromatherapy is a known science all over the world and is a fashion now a days.

Sources of some of the Perfumes introduced by Arabs

White Musk

It forms naturally when certain kinds of granite rocks react under changing weather. This reaction results in yellowish rocks that are called white musk. It is found in some of Indian Mountains.

Cold White Musk

It forms the same way the white musk forms but it is found in some of the cold European Mountains.

Black Musk

The sole source of black musk is the belly button of a female deer. Interestingly, this deer continues to produce musk in a pouch in its belly while in wild and stops as soon as it is under captivity. Just a very recent development in this regard is that someone has succeeded in making the female deer produce black musk in captivity (this might bring the prices of black musk down if succefully done on large scale).

Oud / Agarwood / Aloeswood / Geharoo

The fragrance of Oud forms due to the parasites that live inside the agarwood trees. Agarwood tree is found in India, Cambodia, Vietnam and other rainforests of Far East Asian countries. By a rough estimate 1 kg of pure Essential Oil of Agarwood is priced around US$20,000.00 and $30,000.00. The good Oud is bitter in taste. The bitter the Oud, the finer is its type.

White Amber

It is extracted from the material that the blue whale spits out when it has troubles with its stomach. It is found on the coasts of Ethiopia and Scandinavian countries.

Amber spirit

This one is extracted from the amber flowers that are found in forests of India, where it is distilled and mixed with other perfumes like saffron, rose and others.

Saffron

Saffron flowers are found in Iran, Spain and India. Iranian saffron is considered to be the best then comes the Spanish and Indian. <!--[endif]-->

Taif Rose

King of perfumes! It is extracted from the roses spread over Taif region of Saudi Arabia. It is considered to be one of the best roses on earth due to the gathered climatic circumstances that positively affect the growth of the roses in that area. Experts in a specific season of the year collect the roses. Rose Essential Oil is amongst the few most expensive of the world. Rose Otto and Turkish Rose are other best kinds of roses used in perfume making.

Sandal

Sandalwood is found in some of the forests of southern India, best among them is from Mysore province of Karnataka State. It is a bit whitish wood, of special, attractive smell. It gives beautiful scents when mixed with other Arabic perfumes like Oud, Amber, Saffron and Musk. By itself Sandal Oil is very aromatic and is used for therapeutic purposes too.

The following information taken from the catalogue of a famous perfume maker of Middle East may give good idea about Oud to our readers ;

FROM FUNGUS TO FRAGRANCE

Infection is a nice word for agarwood perfume makers. When a certain kind of tree found in Burma, Cambodia and other far eastern countries are infected with fungus, it marks the beginning of a process, which culminates in some of the world’s finest fragrances. The more severe the infection, the more precious the wood becomes.

This wood, known as Agarwood is extracted from the core of the tree by the skilled staff who undergo serveral yars of rigorous training to undertake this delicate and labourious task. Agarwood is then subjected to an intricate distillation process facilitating the formation of agarwood oil or commonly known as Dehnal oudh, which is the chief ingredient in many popular and expensive eastern and western perfumes.

A History of Fragrance

© 1995 Kathi

Keville, Mindy Green

(Excerpted

from Aromatherapy:

A Complete Guide to the Healing ArtPublished by Crossing Press)

The Ancient World

Much of the ancient history of fragrance is shrouded in mystery. Anthropologists speculate that primitive perfumery began with the burning of gums and resins for incense. Eventually, richly scented plants were incorporated into animal and vegetable oils to anoint the body for ceremony and pleasure. From 7000 to 4000 bc, the fatty oils of olive and sesame are thought to have been combined with fragrant plants to create the original Neolithic ointments. In 3000 bc, when the Egyptians were learning to write and make bricks, they were already importing large quantities of myrrh. The earliest items of commerce were most likely spices, gums and other fragrant plants, mostly reserved for religious purposes.

While on a modern archeological expedition in 1975 to the Indus Valley (which runs the length of modern Pakistan), Dr. Paolo Rovesti found an unusual terra-cotta apparatus, displayed along with terra-cotta perfume containers, in a Taxila museum. It looked like a primitive still, although the 3000 bc dating would place it 4,000 years earlier than most sources date the invention of distillation. Then a vessel of similar design, from around 2000 bc and unquestionably a still, was discovered in Afghanistan. Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets from the 13th century to the 12th century bc describe elaborate egg-shaped vessels containing coils; again, their function is unknown, but they are quite similar to Arab itriz used much later in the history of the region for distillation.

Even if essential oils were available at such an early date, most man-made fragrance was still in the form of incense and ointments. During the reign of the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid (c. 2700 bc), papyrus manuscripts recorded the use of fragrant herbs, choice oils, perfumes and temple incense, and told of healing salves made of fragrant resins. Throughout the African continent people coated their skin with fragrant oils to protect themselves from the hot, dry sun. This practice extended to the Mediterranean, where athletes were anointed with scented unguents before competing.

From this same era, the Epic of Gilgamesh tells of the legendary king of Ur in Mesopotamia (modem Iraq) burning ntyw, incense of cedarwood and myrrh to put the gods and goddesses into a pleasant mood. A tablet from neighboring Babylonia contains an import order for cedar, myrrh and cypress; another gives a recipe for scented ointments; a third suggests medicinal uses for cypress. Still farther east, the Chinese Yellow Emperor Book of Internal Medicine, written in 2697 bc, explains various uses of aromatic herbs.

Trade routes to obtain fragrant goods were established throughout the Middle East well before 1700 bc and would be well-traveled for the next 30 centuries-until the Portuguese discovered a way around the Cape of Good Hope. The Old Testament describes one group of early traders: "a company of Ishmaelites [Arabs] from Gilead, bearing spicery, balm and myrrh, going to carry it down to Egypt." Perhaps as early as 1500 bc, monsoon winds began carrying double-outrigger canoes along the "cinnamon route."

Egypt's penchant for producing unguents and incense was to become legendary. A figure of King Thothraes IV, carved into the base of the Sphinx at Giza, has been offering devotional incense and oil libations since 1425 bc, and there is little doubt that Egyptian aromas were potent: calcite pots filled with spices such as frankincense preserved in fat still gave off a faint odor when opened in King Tutankhamen's tomb 3,000 years later. As depicted on wall paintings, solid ointments of spikenard and other aromatics, called "bitcones," were placed on the heads of dancers and musicians, where they were allowed to gradually-and dramatically-melt down over hair and body.

The most famous Egyptian fragrance, kyphi (the name means "welcome to the gods"), was said to induce hypnotic states. The City of the Sun, Heliopolis, burned resins in the morning, myrrh at noon and kyphi at sunset to the sun god Ra. Kyphi had more than religious uses, however. It could lull one to sleep, alleviate anxieties, increase dreaming, eliminate sorrow, treat asthma and act as a general antidote for toxins. Several recipes are recorded, one of the oldest being a heady blend of calamus, henna, spikenard, frankincense, myrrh, cinnamon, cypress and terebinth (pistachio resin), among other ingredients. Cubes of incense were prepared by mixing ground gums and plants with honey, similar to a technique used by the Babylonians and later adapted by both Romans and Greeks.

The ancient Hebrews employed fragrance to consecrate their temples, altars, candles and priests. The book of Exodus (c. 1200 bc) provides the recipe for the holy anointing oil given to Moses for the initiation of priests: myrrh, cinnamon and calamus, mixed with olive oil. Although Moses decreed severe punishment for anyone who obtained holy oils and incense for secular use, not all aromatics were restricted to religious use. We learn in the book of Proverbs that "ointment and perfume rejoice the heart" (27:9), while in the Song of Solomon we read:

A bundle of myrrh is my beloved unto me;

He shall lie all night between my breasts

My beloved is unto me as a cluster of camphire [henna]

In the vineyards of En-gedi. (1:13-14)

By the late 5th century, Babylon was the principal market for the perfume trade. The Babylonians used cedar of Lebanon, cypress, pine, fir resin, myrtle, calamus and juniper extensively. When the Jews returned from captivity in Babylon, they brought back a heightened appreciation of fragrance, especially in the form of incense.

The ancient Greek world was also rich in fragrance. Just one Greek word, arómata, describes incense, perfume, spices and aromatic medicines. One such concoction, manufactured by a perfumer named Megallus, was the legendary megaleion, which contained burnt resin, cassia, cinnamon and myrrh, and was used in the treatment of wounds and inflammation. At Delphi, the oracle priestesses sat over smoldering fumes of bay leaves to inspire an intoxicating trance; holes in the floor allowed the smoke to "magically" surround them.

By the 7th century bc, Athens had developed into a mercantile center in which hundreds of perfumers set up shop. Trade was heavy in fragrant herbs such as marjoram, lily, thyme, sage, anise, rose and iris, infused into olive, almond, castor and linseed oils to make thick unguents. These were sold in small, elaborately decorated ceramic pots, similar to the smaller jars still sold in Athens today.

While Socrates heartily disapproved of perfume, worrying that it might blur distinctions between slaves (who smelled of sweat) and free men (who apparently did not), Alexander the Great-who, when he entered the tent of the defeated King Darius after the battle of Issos, contemptuously threw out the king's box of priceless ointments and perfumes-learned to love aromatics after a few years traveling in Asia. He sent deputies to Yemen and Oman to find the source of the Arabian incense with which he anointed his body and which burned constantly by his throne. To his Athenian classmate Theophrastus he sent plant cuttings obtained during his extensive travels, thus establishing a botanical garden in Athens. Theo-phrastus' treatise On Odors covered all the basics: blending perfumes, shelf life, using wine with aromatics, properties that carry scent, and the effect of odor on the mind and body.

As trade routes expanded, Africa, South Arabia and India began to supply spikenard, cymbopogons and ginger to Middle Eastern and Mediterranean civilization; Phoenician merchants traded in Chinese camphor and Indian cinnamon, pepper and sandalwood; Syrians brought fragrant goods to Arabia. True myrrh and frankincense from distant Yemen finally reached the Mediterranean by 300 bc, by way of Persian traders. Traffic on the trade routes continued to swell as demand increased for roses, sweet flag, orris root, narcissus, saffron, mastic, oak moss, cinnamon, cardamom, pepper, nutmeg, ginger, costus, spikenard, aloewood, grasses and gum resins.

By the 1st century ad, Rome was going through about 2,800 tons of imported frankincense and 550 tons of myrrh per year. Nero, Roman emperor in 54 ad, spent the equivalent of $100,000 to scent just one party he was giving. Carved ivory ceilings in his dining rooms were fitted with concealed pipes that sprayed down mists of fragrant waters on guests below, while panels slid aside to shower guests with fresh rose petals. (All this fragrant excess wasn't without its casualties; one unfortunate guest is said to have been asphyxiated by a dense cloud of those petals.) Both men and women literally bathed in perfume while attended by slaves called cosmetae. Three types of perfume were applied to the body: solid unguents, scented oil and perfumed powders, all purchased from the shops of unguentarii, who were regarded every bit as highly as doctors. The Romans even referred to their sweethearts as "my myrrh" and "my cinnamon," much as we use the gustatory endearments "honey" and "sweetie pie."

The Roman historian Pliny, author of the impressive lst-century ad Natural History, mentions 32 remedies prepared from rose, 21 from lily, 17 from violet and 25 from pennyroyal. Famous Roman blends of the era included susinon, which served not only as a perfume but was a diuretic and women's anti-inflammatory tonic, and amarakinon, used to treat indigestion and hemorrhoids, and to encourage menstruation. A similar spikenard ointment was suggested for coughs and laryngitis.

Fragrance occurs, at least symbolically, throughout the New Testament records. The frankincense and myrrh brought to the Christ child were more valuable than the gift of gold (if indeed it was gold; some New Testament scholars speculate that the three wise men may have been carrying gold-colored, fragrant ambergris). One of the most famous gospel scenes involves Judas Iscariot complaining about Mary Magdalene's anointing of Christ's feet with costly spikenard. Even the Greek word for Christ, Christos, means "anointed," from the Greek chriein, to anoint.

Indeed, the 1st century ad was a time of accelerated development of aromatherapy's source sciences. Aromatics was one of five sections covered in Dioscorides' famous Herbal. The first written description of a still in the Western world is of one invented by Maria Prophetissima and described in The Gold-Making of Cleopatra, an Alexandrian text from around the first century. (Her design was used initially to distill essential oils, but also proved useful for alcoholic beverages.) Gnostic Christians from the 1st to the 4th century ad, whose beliefs were deeply rooted in Egyptian philosophy, held fragrance in high regard. Seeking release from the limitations of the material world, they embraced the symbology of essential oils, which represented the soul of the plant.

Orientalia

Distillation of essential oils and

use of aromatics also progressed in the Far East. Like the Christian Gnostics,

Chinese Taoists believed that extraction of a plant's fragrance represented the

liberation of its soul. Like the Greeks, the Chinese had just one word, heang,

for perfume, incense and fragrance. Moreover, heang was classified into six

basic types, according to the mood induced: tranquil, reclusive, luxurious,

beautiful, refined or noble.

The Chinese upper classes made lavish use of fragrance during the T'ang dynasties, which began in the 7th century ad, and continued to do so until the end of the Ming dynasty in the 17th century. Their bodies, baths, clothing, homes and temples were all richly scented, as were ink, paper, sachets tucked into their garments, and cosmetics. The ribs of fans were carved from fragrant sandalwood. Huge, fragrant statues of the Buddha were carved from camphor wood. Spectators at dances and other ceremonies could expect to be pelted with perfumed sachets. China imported jasmine-scented sesame oil from India, Persian rosewater via the silk route and, eventually, Indonesian aromatics-cloves, gum benzoin, ginger, nutmeg and patchouli-through India.

Numerous texts related to aromatherapy were published in China. The Hsian Pu treatise by Hung Chu (1100 ad) describes incense-making. The 16th century saw publication of the famous Chinese Materia Medica Pen Ts'ao, which discusses almost 2,000 herbs, including a separate section on 20 essential oils. Jasmine was used as a general tonic; rose improved digestion, liver and blood; chamomile reduced headaches, dizziness and colds; ginger treated coughs and malaria.

It was the Japanese, however, who turned the use of incense into a fine art, even though incense didn't arrive in Japan until very late, around 500 ad. (The Japanese by then had perfected a distillation process.) By the 4th to 6th century, incense pastes of powdered herbs mixed with plum pulp, seaweed, charcoal and salt were pressed into cones, spirals or letters, then burned on beds of ashes. Special schools taught (and still teach) kodo, the art of perfumery. Students learned how to burn incense ceremonially and performed story dances for incense-burning rituals.

From the Nara through the Kamakura Periods (710-1333), small lacquer cases containing perfumes hung from a clasp on the kimono. (The container for today's Opium brand perfume was inspired by one of these.) An incense-stick clock changed its scent as time passed, but also dropped a brass ball in case no one was paying attention. A more sophisticated clock announced the time according to the chimney from which the fragrant smoke issued. Geisha girls calculated the cost of their services according to how many sticks of incense had been consumed.

The Middle Ages

The spread of Islam helped to expand appreciation and knowledge of fragrance. Mohammed himself, whose life spanned the 6th and 7th centuries, is said to have loved children, women and fragrance above all else. His favorite scent was probably camphire (henna), but it was the rose that came to permeate Moslem culture. Rose water purified the mosque, scented gloves, flavored sherbet and Turkish delight, and was sprinkled on guests from a flask called a gulabdan. Prayer beads made from gum arabic and rose petals released their scent when handled.

Following the translation in the 7th century of the Western classics into Arabic, Arab alchemists in search of the "quintessence" of plants found it represented in essential oils. The Book of Perfume Chemistry and Distillation by Yakub al-Kindi (803-870) describes many essential oils, including imported Chinese camphor. Gerber (Jabir ibn Hayyan) of Arabia, in his Summa Perfectionis, wrote several chapters on distillation. Credit for improving (and sometimes, erroneously, for discovering) distillation goes to Ibn-Sina, known in the West as Avicenna (980-1037), the Arab alchemist, astronomer, philosopher, mathematician, physician and poet who wrote the famous Canon of Medicine. Essential oils were used extensively in his practice, and one of his 100 books was devoted entirely to roses.

The 13th-century text by Arab physician Al-Samarqandi was also filled with aromatherapeutic lore, with a chapter on aromatic baths and another on aromatic salves and powders. Steams and incenses of marjoram, thyme, wormwood, chamomile, fennel, mint, hyssop and dill were suggested for sinus or ear congestion. Herbs were burned in a gourd, breathed as vapors, or sprinkled on hot stones or bricks. In India, the 12th-century text Someshvara described a daily bath ritual in which fragrant oils of jasmine, coriander, cardamom, basil, costus, pandanus, agarwood, pine, saffron, champac and clove-scented sesame oil were applied. Participants in Tantric ceremonies were also anointed with oils, the men with sandalwood, the women with a bouquet of jasmine on the hands, patchouli on the neck and cheeks, amber on the breasts, spikenard in the hair, musk on the abdomen, sandalwood on the thighs and saffron on the feet. In other rituals, women called dainyals held cloths over their heads to capture Tibetan cedar smoke, which would send them into prophetic chanting. Special finger rings held small compartments filled with musk or amber. Indian temple doors carved from sandalwood invited worshippers to enter (and conveniently deterred termites).

In Europe, a shining light of the Middle Ages was the Abbess of Bingen, Saint Hildegard (1098-1179), an herbalist whose four treatises on medicinal herbs included Causae et Curae ("Causes and Cures of Illness"), in which she spoke highly of fragrant herbs-especially of her favorite, lavender. (Some sources credit her with the invention of lavender water.) European nuns and monks closely guarded the formulas for "Carmelite water," which contained melissa, angelica and other herbs, and for aqua mirabilis, a "miracle water" used to improve memory and vision, and to reduce rheumatic pain, fever, melancholy and congestion.

From the 9th century to the 15th century, the Medical School of Salernum (Salerno) in Italy drew scholars from both the West and the East and crowned its graduates with bay-laurel wreaths. Here much Western knowledge, preserved and refined by the Moslems after the fall of Alexandria, was reestablished in the West. The school's Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum was a kind of medical Bible for many centuries.

Influence of the Spice Trade

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Italy monopolized the Eastern trade established during the Crusades. The guilds-grocers, spicers, apothecaries, perfumers and glovers-controlled the import of enormous quantities of spices used to disinfect cities against the plague and other maladies. The purpose of Marco Polo's journey to China was to bypass Moslem middlemen and their 300-percent markup in price by convincing the Orient to trade directly with Genoa. When Christopher Columbus stumbled on the New World, he intended to make Spain a bigger player in the spice trade by beating out the competition. His route to the East was shorter. Tobacco, coca leaves, vanilla, potatoes and chilies of the Americas were of great interest to the rest of the world. Columbus kept looking for cloves and cinnamon but never did find these spices.

It was the good fortune of the Portuguese to finally establish a route around the tip of Africa, or "Cape of Storms" (later renamed "Cape of Good Hope"). In 1498, Vasco de Gama's sailors cheered, "Christos e espiciarias!" ("For Christ and spices!") as they neared India and her wealth of cloves, ginger, benzoin and pepper. (Jealous, Venice persuaded the Moslem traders to fight the Portuguese, who now controlled the spice trade. The Moslem traders were not successful.) The trade thus shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic.

India-always prominent in the spice trade, although more as a pawn than a player-offered a rich variety of scents, including 17 types of jasmine alone. (The Moslem ruler Barbur, one of India's Mogul kings, declared, "One may prefer the fragrances of India to those of the flowers of the whole world.") The British, following the lead of the Dutch East India Company, finally attained a share of the action in the 18th century by taking control of India by exploiting the friction between the Moslems and Hindus. The British published an extensive set of volumes on medicinal and fragrant botanicals titled The Wealth of India.

The Americas

Columbus's assumptions were correct in one respect at least. The Americas indeed held fragrant treasures: balsam of Peru and Tolu, juniper, American cedar, sassafras, and tropical flowers like vanilla, heady with perfume. Like other indigenous peoples around the world, the Native Americans had a long history of burning incense and using scented ointments. Throughout the Americas, massage with fragrant oils was a common form of therapy.

The Aztecs were as extravagant with incense as the Egyptians, and they too manufactured ornate vessels in which to burn it. Injured Aztecs were massaged with scented salves in the sweat lodges, or temazcalli. The Incas made massage ointments of valerian and other herbs thickened with seaweed. In Central America, the Mayans steamed their patients one at a time in cramped clay structures.

Throughout the continent, North Americans "smudged" sick people with tight bundles of fragrant herbs or braided "sweet grass" (Hierochloe odorata), which smells like vanilla. Congestion, rheumatism, headaches, fainting and other ills were treated with smoke from burning plants, or with a strong herb infusion thrown over hot rocks to produce scented steam. The people of the Great Plains used echinacea as a smoke treatment for headaches; many tribes used pungent plants such as goldenrod, fleabane and pearly everlasting for therapeutic purposes.

Scents and "Sophistication"

Even after losing control over the spice trade, Italy remained the European leader for cosmetics and perfumes. As Venice became more cosmopolitan, it began to produce scented pastes, gloves, stockings, shoes, shirts and even fragrant coins. Our word "pomander" comes from the French words pomme d'ambre, a scented ball made of ambergris, spices, wine and honey, carried in a perforated container carried on the belt or on a string around the neck. Dried medicinals were stored in beautiful porcelain pots, and botanical waters were kept in Venetian glass.

The Italian influence swept through France, helped along by Caterina de Medici's marriage to France's Prince Henri II. Making the journey with her were her alchemist (who probably also made her poisons too, but that's another story) and her perfumer, who set up shop in Paris. The towns of Montpellier and Grasse, already strongly influenced by neighboring Genoa, had long produced the perfumed gloves that were in high style among the elite. (The gloves were most often perfumed with neroli, or with animal scents such as ambergris and civet. Apparently this wasn't always appreciated. A 17th-century dramatist, Philip Massinger, complained: "Lady, I would descend to kiss thy hand/but that 'tis gloved, and civet makes me sick.") These towns took the lead, as France's growing fragrance trade began to predominate over Italy's.

England was also influenced by the Italian love of scent. A pair of scented gloves so captured the attention of Queen Elizabeth I, she had a perfumed leather cape and shoes made to match. Sixteenth-century Elizabethans powdered their skin, hair and clothes with fragrant powders, and toned their skin with scented vinegars and fragrant waters. These waters like the Roman blends doubled as internal medicines.

The number of plants distilled expanded in the 16th century, and many books appeared on alchemy and the art of distillation. In 1732, when the Italian Giovanni Maria Farina took over his uncle's business in Cologne, he produced aqua admirabilis, a lively blend of neroli, bergamot, lavender and rosemary in rectified grape spirit. This was splashed on the skin, and also used for treating sore gums and indigestion. French soldiers stationed there dubbed it eau de Cologne, and Napoleon is said to have gone through several bottles a day-an endorsement that made it so popular that 39 competitors and a half century of law suits resulted. Other fashionable fragrances included rose, violet and patchouli, which were used on the imported Indian shawls made popular by Napoleon's famous consort, Josephine.

The Modern World

In the 19th century, two important changes occurred in the Western world of fragrance. The 1867 Paris International Exhibition exhibited perfumes and soaps apart from the pharmacy section, thus establishing an independent commercial arena for "cosmetics." Even more significant was the production of the first synthetic fragrance, coumarin (which smells of new-mown hay), in 1868, followed 20 years later by musk, vanilla and violet. Eventually this list expanded to many hundreds, then thousands, of synthetic fragrances-the first perfumes unsuitable for medicinal use.

France became the leader in reestablishing the therapeutic uses of fragrance. The perfume industry had been divorced from medicinal remedies for 50 years, but slowly began to reclaim its medicinal heritage. The term "aromatherapy" was coined in 1928 by French chemist Rene-Maurice Gattefoss‚. His interest in using essential oils therapeutically was stimulated by a laboratory explosion in his family's perfumery business, in which his hand was severely burned. He plunged the injured hand into a container of lavender oil and was amazed at how quickly it healed.

By the 1960s, a few people, including the French doctor Jean Valnet and the Austrian-born biochemist Madame Marguerite Maury, were inspired by Gattefoss‚'s work. As an army surgeon in World War II, Dr. Valnet used essential oils such as thyme, clove, lemon and chamomile on wounds and burns, and later found fragrances successful in treating psychiatric problems. But while Valnet helped inspire a modern aromatherapy movement when his book Aromatherapie was translated into English as The Practice of Aromatherapy, it was the appearance in 1977 of masseur Robert Tisserand's book The Art of Aromatherapy, strongly influenced by the work of Valnet and Gattefoss‚, that was successful in capturing American interest. At present, there are many books available on aromatherapy.

Most important, the efforts of pioneers like Valnet, Maury and Tisserand have turned aromatherapy into a disciplined healing art, rediscovering the uses of fragrance from ancient times and sparking a revival of aromatherapy that has swept throughout the world.

Sandalwood

Sandalwood - The most renowned sandalwood oil, and the sandalwood oil of history, is distilled from the Sandalwood tree of India and Indonesia (Saiilalum album — Sirium myrlifolium), the best coming from Mysore. This tree, also called White Sandalwood, is a parasitic plant, attaching suckers to the roots of other trees, and grows up to 30 feet high. The oil is also called Sanders, White Sanders, Yellow Sanders, Citron Sanders and Santal. The oil is contained in the heartwood and is obtained only from very mature trees after they have been felled. The harvesting of sandalwood is now tightly controlled bv the Indian Government. White Sandalwood is sometimes confused with Red Sandalwood (Adciitwthcra ytmmiua), winch provides a useful red hardwood but is not aromatic.

Sandalwood oil, which is clear, viscid and Strongly aromatic, is steam-distilled from the wood chippings, 1 cwt of wood providing about 30 oz of oil. It is often called Sandal. It retains its odour for a long time and is an excellent fixative. It has for long been one of the principal materials of Indian perfumery, being used both as a fragrance and, when dissolved in spirit, as a base for other fragrances. It is much used in incenses. As it assimilates very well with rose, it is sometimes used in India mixed with Attair of Roses. In western perfumery it is one of the most valuable (and expensive) of raw materials available, being found in the base notes of many types of perfume and used to give classic notes to chypre, fougsere and oriental-type perfumes. It appears as a principal ingredient in over 50% of all women's quality perfumes, and some 30% of men's fragrances.